Welcome to Easel for Digital Images©, a different kind of digital imaging tool.

What makes Easel different? Most digital imaging tools reproduce and improve upon tools that photographers have used for a long time -- darkroom, album, slide projector, etc. Easel, on the other hand, is designed to let you do things that are hard to do (and hence rarely done) with non-digital images. Easel strives to do intrinsically digital things.

With Easel's ability to easily manipulate and combine multiple images with other graphical and textual elements, the closest analogy may be the scrapbook. Users will discover quickly, however, that Easel is more than a tool for digital scrapbooking (though it does work well for that).

Another thing that sets Easel apart is its ability to create large, very high resolution printed output. If you have a photo-quality printer that can handle 8"x10" or larger (13"x19" really gets people's attention), prepare to be stunned by the quality of what Easel can do with it. But if not, don't worry; just select the Online Printer and e-mail your print jobs to the online photo sites. Imagine a 20"x30" poster, with the resolution of a high res photo, for about $20. I've been giving these for presents lately, and friends, family, and coworkers just love them. See Using Online Printers for details.

Note: The entry-level Easel 8x10 Edition limits you to smaller pages.

For background on the creation of Easel, read on. If you don't care about such trivia, go to Getting Started.

A few years ago, my wife complained that she saw very few of the many pictures that I took with my new digital camera. I explained that digital pictures are much easier to take than to print, and that one reason I took so many was that once you've bought the camera, the pictures are free until you print them. I invited her to view them on my PC the way I did, and even offered to do a slide show on the TV. She did not find this satisfactory, because she wanted something to tack to the bulletin board. I printed a bunch of snapshots and up they went.

She was happy, but now I was unsatisfied. The snapshots looked fine, almost as good as film (photo printers weren't as good back then), but that was part of the problem. I had been taking pictures and programming computers for years. I was thrilled with my digital camera and the possibilities that digital imaging seemed to offer, but the best I could do was the same thing I had been doing with film? I wanted to do things that couldn't be done with film photography, at least not easily. I wanted things on the bulletin board that would prompt people to ask "How did you do that?"

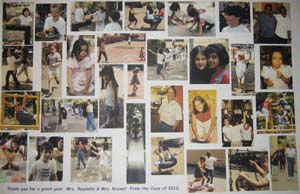

I was contemplating what sort of earth-shattering digital innovation I was going to come up with when my son's kindergarten teacher asked someone to take pictures of the class, which I did. When I brought her a pile of snapshots, she asked if I could "make some sort of poster." She was thinking along the lines of poster board, scissors, and rubber cement; but then the proverbial light bulb came on over my head. I had, after all, just bought a color printer that could handle 13x19 inch paper. I practically ran home, fired up Adobe® Photoshop®, and started cutting and pasting.

It did not take long to realize that Photoshop, truly

awesome in its ability to edit single images, was not the right tool for

this job. The two biggest problems were that a) as soon as I pasted in

an image, it became part of one big image, meaning that I lost the ability

to manipulate (move, crop, resize, lighten, etc) it individually, and

b) the single image grew so large that the computer slowed to a crawl

and eventually began crashing. I could reduce the file to a workable size

by reducing the resolution of the original images, but the whole point

was to produce a film-quality composition. I struggled along for many

evenings, eventually creating a 65 megabyte image that sacrificed some

quality, took 5 minutes to load and 55 minutes to print, and crashed Photoshop

frequently, including everytime I tried to make more than one change without

saving, quitting, and restarting.

It did not take long to realize that Photoshop, truly

awesome in its ability to edit single images, was not the right tool for

this job. The two biggest problems were that a) as soon as I pasted in

an image, it became part of one big image, meaning that I lost the ability

to manipulate (move, crop, resize, lighten, etc) it individually, and

b) the single image grew so large that the computer slowed to a crawl

and eventually began crashing. I could reduce the file to a workable size

by reducing the resolution of the original images, but the whole point

was to produce a film-quality composition. I struggled along for many

evenings, eventually creating a 65 megabyte image that sacrificed some

quality, took 5 minutes to load and 55 minutes to print, and crashed Photoshop

frequently, including everytime I tried to make more than one change without

saving, quitting, and restarting.

On the other hand, when I tacked a big print of it on the kindergarten bulletin board, virtually every parent asked a) "How did you do that?" and b) "Can I have a copy?" So the process had been bad but the outcome was good. I searched for a good software tool to fix the process, concluded that none existed and, sensing an opportunity, resolved to create one. Easel, which does much more (and took much longer) than I originally planned, is the result.